Hong Kong Property

Long before it was popular to announce to your shareholders that you were pivoting to a bitcoin treasury strategy, every HK-listed company had a real estate investment business.

And for about three decades, who could blame them? Hong Kong property only went one way. Every crisis: the Asian Financial Crisis, SARS, and the Global Financial Crisis were all buying opportunities. And it made sense. Hong Kong’s favorite national pastime wasn’t horse racing; it was buying property with maximum conviction.

The current downturn, however, has been different. You can practically timestamp the top of the last commercial real estate cycle. In 2018, Li Ka-Shing’s CK Asset sold The Center, a literal skyscraper in Central, for HKD 40 billion.

The first shoe to drop was the 2019 umbrella protests, which prompted foreign firms to relocate their Asia headquarters elsewhere, such as Singapore. Then came Covid, further destroying the idea that you need big towers with small cubicles to write emails.

Finally, HK followed America’s lead in the rate increases between March 2022 and July 2023, which put the final nail in the coffin. The protests pushed companies out, COVID eliminated the need for offices, and higher rates crushed the economy. Three consecutive blows, each worse than the last.

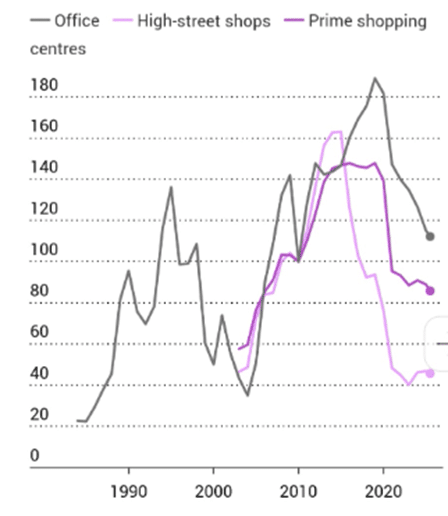

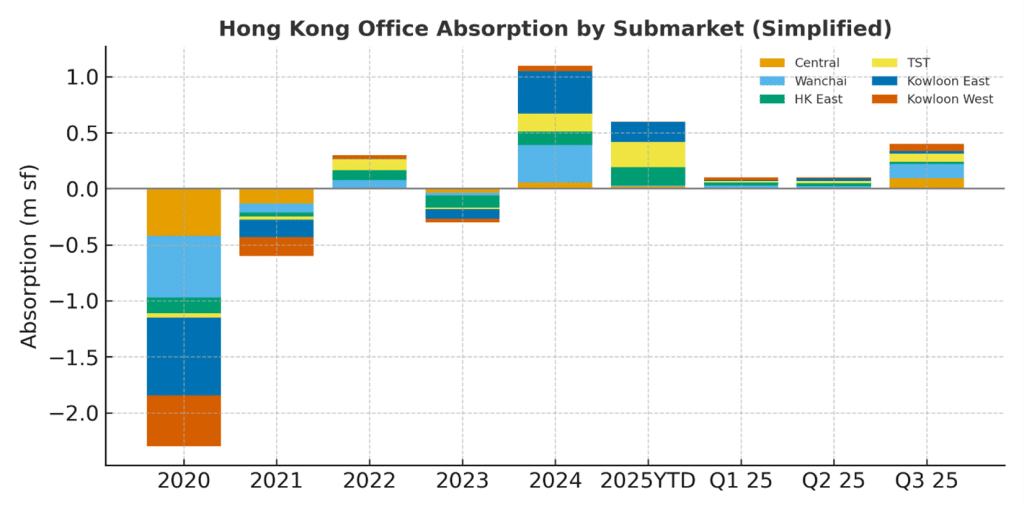

Unsurprisingly, the result looks like a slow-motion margin call. Prime offices are down about 50% from the 2018 peak, rents are down 23%, and vacancy is north of 13%. Net absorption has been negative for years at roughly -2.9 million square feet since 2020.

But cycles don’t stay frozen forever. So why are we bullish on HK real estate?

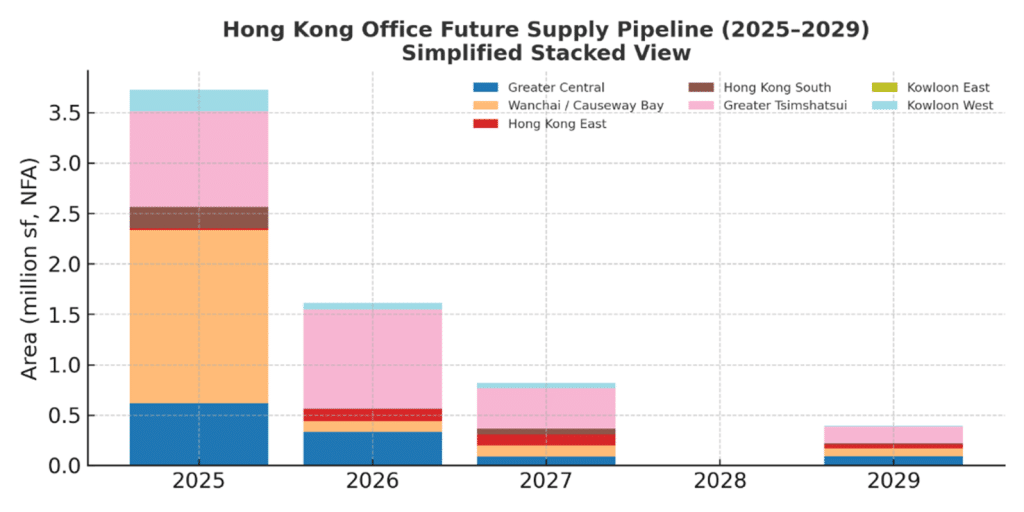

For starters, let’s look at the supply situation. Newspaper headlines will tell you there is still an ample supply coming online between now and 2028. But if we zoom in, we see that 2026 is the last year with significant supply (1.4m sq ft), followed by a sharp drop starting in 2027. There are some 2027 completions in Kowloon, which shouldn’t really impact property prices in Central.

Absorption of this new supply has been slowly recovering. Q3 actually came in at +0.4m sq ft, helped by a recovering HK IPO market and financial industry. Will HK be able to absorb 1.5m sq ft of new supply annually?

In other words: 2026 is peak supply, 2027 thins out, and 2028 flips to shortage.

Then there’s policy. Commercial office prices don’t require emergency government intervention because nobody votes based on how underwater the landlord of Lee Garden One is. But broadly stabilizing the property market is a political hobby in Hong Kong, and the government is rolling out the usual toolkit.

They’ve paused commercial land sales for a year. They’re re-purposing some commercial sites. They’re converting hotels into student housing. It’s not sweeping reform, but it’s a push in the right direction.

By the third quarter of this year, rents in Central showed the first signs of stabilization. After years of relentless decline, even a pause feels like momentum.

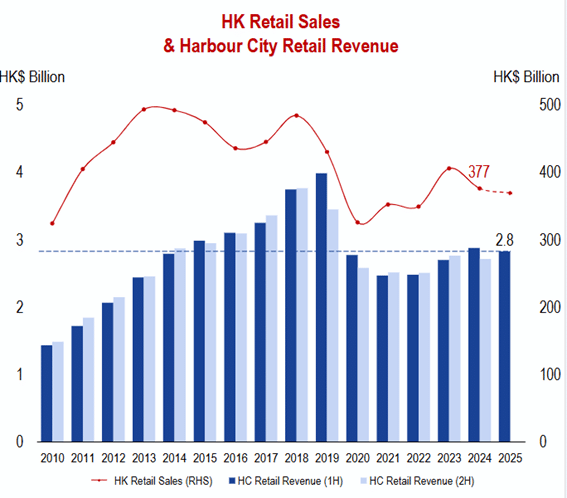

The picture for retail is slightly different. For decades, Hong Kong was the closest thing mainland Chinese consumers had to an open market. No import tariffs, no fake goods (well, fewer fakes), and no moral judgment when you buy a dozen Rolexes “for friends.” The mainland had money but no access; Hong Kong had access but no shame in taking your money. It was a perfect symbiosis.

In the 2000s and 2010s, this basically turned into a national sport. Tour groups would arrive from Shenzhen, cross the border, and fill Tsim Sha Tsui with a steady stream of UnionPay cards. The city became an air-conditioned tax haven for handbags: Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Cartier. All tax-free and authentic, with customer service that didn’t yell at you.

But Southbound tourism has slowed, and mainland tourists are more focused on experimental travel. Shopping for handbags is just as much fun in Paris or in our duty-free Hainan (yes, Beijing built its own Hong Kong, minus the protests).

Vacancies in prime shopping centers rose to 10.5%. Luxury brands are being replaced by pharmacies, stockbrokers, and mid-range apparel makers. The Patek Philippe store on Russell Street has been replaced by a Skechers store, which pays 35% lower rent.

Look closely enough at the supply–demand curve, and you can still sketch out a stabilization story. Retail in Hong Kong isn’t dead; it’s simply evolving, rediscovering what it wants to be without the tour buses dictating the script. And while the city is no longer the automatic shopping capital of China, Hong Kong still has the brand depth, infrastructure, and footfall to rebuild a healthier, more sustainable retail mix. Call it cautious optimism: not a moonshot, but a market that finally has room to get better.

During our trip to HK, we met with the management of both Hysan and Wharf REIC. Wharf REIC owns the iconic Harbour City and Times Square, and is more of a retail play (2/3 retail, 1/3 office). Hysan owns some of the most prestigious office buildings in Causeway Bay and has a large development asset in Lee Garden 8, the largest property to be delivered in 2026. Both sports FCF yields in the 10% range, which is arguably too high for the highest-quality CRE on the island, especially with Hibor hovering around 3%. At 10% FCF yields on trophy assets, you don’t need a heroic recovery, just a mildly less pessimistic one. That alone should be enough for a re-rating.