The No-Earnings Companies

A low frequency but juicy strategy where the edge is government incompetence.

Let’s dig in…

The No-Earnings Companies

Starting off this week’s theme, we were reminded of an old article by Erik that really challenged the way we think. In his piece titled “Stop caring about earnings” (paywall removed for KEDM subscribers), he explained how Warren Buffett pioneered the no-dividend company. Prior to Berkshire, investors expected companies to return capital in the form of dividends. The idea that a company would retain all cash and reinvest it on behalf of investors was revolutionary. BRK could hypothetically pay out its cash any time it wanted. It just chose not to.

And it worked. BRK retained its cash, avoided paying taxes on its dividends, and made all its early investors rich.

Similarly, Erik argued that Jeff Bezos pioneered a new paradigm: one where profits are tax-inefficient and shareholder value is maximized if all cash is reinvested in the business. Reported profits would be zero. Value investors would short your stock and talk about the market being in a bubble, but meanwhile, their grandkids would order their TP and sign up for the streaming service of the same company.

Naturally, this went against everything we believed. As fundamental investors, we grew up caring about FCF, and we have a healthy skepticism for companies that promise future profitability without showing any FCF today. Frankly, we still aren’t fully convinced, but we’re happy to entertain the idea.

Let’s look at examples.

Amazon is the obvious one and requires little explanation. By foregoing profits, Amazon is now the retailer that can offer goods at the lowest prices and with the shortest delivery times. And even if another store offers it cheaper, do we really trust their returns policy, and do we want to share our credit card data? AMZN chose to reinvest in its business, but if tomorrow Bezos decides he wants to milk the company, this will be a cash cow.

A less obvious example is Booking.com. BKNG has long been one of the largest customers at Google, paying billions for ads which built them a customer base. Years later, customers choose to book directly with BKNG, expecting a loyalty discount and enjoying the fast booking process.

But for every success story, we can think of a dozen companies where profitability remained forever aspirational.

Think of all the companies talking about LTV and CAC. Because investors don’t like the fact that they can’t calculate a ROIC on a company’s investments, those companies have resorted to Voodoo Math to explain their business decisions. As long as a customer’s Lifetime Value (LTV) materially exceeds the Customer Acquisition Costs (CAC), they argue they should blow all their cash on Google ads.

This math falls apart because, in many cases, LTV / CAC aren’t static. LTV for a DoorDash customer might have been high in 2021, but 2 years later, all it took was a $2.50 coupon from Uber Eats to prompt a customer to switch. Meal delivery companies had invested in acquiring customers, but the customer relationship wasn’t sticky.

What differentiates BKNG and AMZN from meal delivery? It’s the stickiness of the customer. There are switching costs. There are benefits of scale, and the industry winner has reached such a scale that no new entrant will ever be able to undercut it on price. In other words, they reinvested the cash not because it fit a mathematical equation, but because it built a moat.

Payments

Now where’s the investment angle? For that, let’s shift gears and talk payments. Specifically, cross-border payments or remittance.

In the old days, José Hernández would walk into a Western Union store and hand over his hard-earned cash. A few days later, Grandmother Hernández would pick it up at the local bodega. He would pay 5% in fees, which was split between the two store owners.

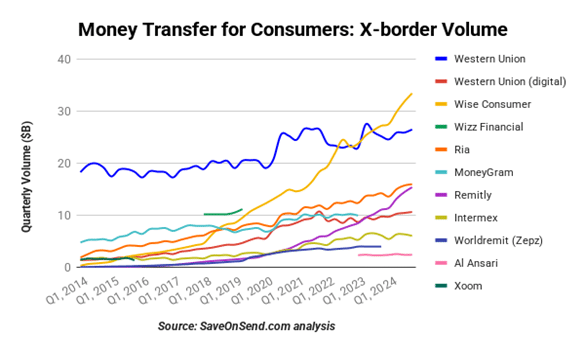

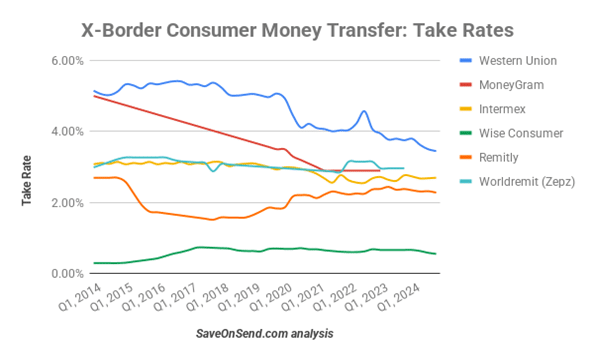

Then, 20 years ago, the digital disruptors emerged. They aggressively undercut the legacy store operators on price, often charging around 2%. As is often the case, the legacy operator couldn’t cut their prices in half without upsetting Wall Street, meaning they lost market share.

The economics of the digital model are different. The required tech investments and absence of physical intermediaries mean that most of the costs to enable a transaction are now fixed. With high fixed costs, economies of scale become more relevant. While this argues for a winner-takes-most market, the remittance market remains highly fragmented.

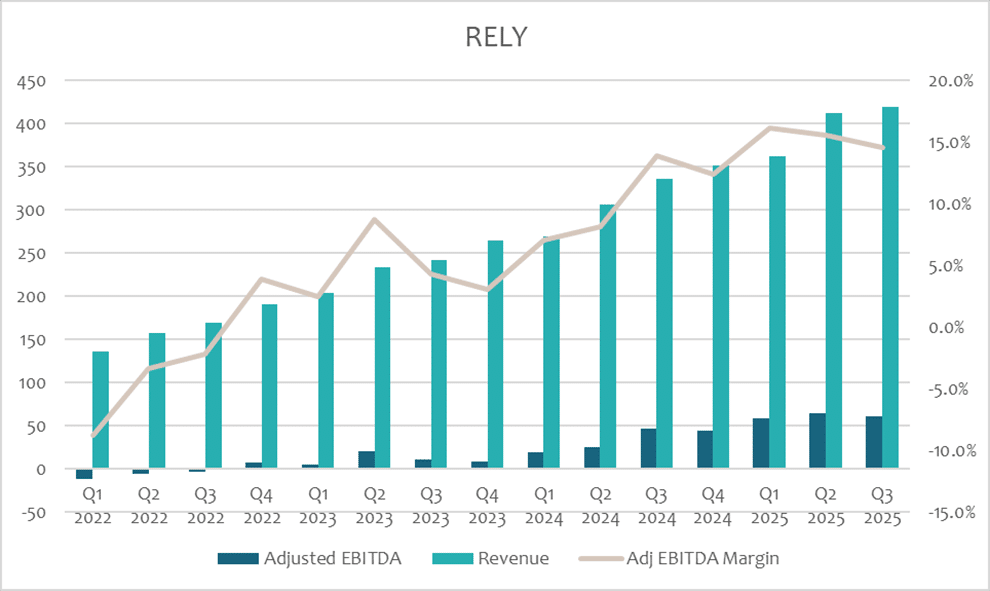

Because they all aspire to be the sole survivor, all money gets reinvested in marketing. This creates a situation where some of those companies could be very profitable today, but they just choose to reinvest. Let’s look at Remitly, a digital remittance pureplay that dominates the market together with Ria (EEFT) and WISE (yes, we know they are largely B2B, but bear with us). In the last quarter, they reported $61m in EBITDA, but this was after $91m in marketing spend. This marketing spend allowed RELY to grow 25% YoY. Their Adjusted EBITDA feels a little ‘fake’ due to high stock-based compensation, but roll your model forward by 1 year, and this SBC is largely offset by a year of growth.

Now the main question to ask is: are customers sticky and is marketing therefore a discretionary spend? Could RELY grow for 1 or 2 more years, then pull back marketing spend to a sustaining level, thereby doubling profitability? Or do they reach a scale where word of mouth becomes more effective than Google ads, allowing them to further save on marketing spend?

A big difference with meal delivery companies is that demand for remittance is based on trust. If you’ve ever walked into a WU store only to walk out with $500 of fake bills, you’ll know what we mean. Customers are price-sensitive, but only to the extent that they can be 100% sure their money will arrive.

There is another way to reinvest in this business: share the improving economics enabled by your scale benefits with your customers. Assuming the customer is price-sensitive, this will help lock in the customer. This seems to be the path that Wise is on. Wise is an imperfect peer to RELY because they’re larger in the B2B cross-border transactions. But everyone who’s had to pay $75 international wire fees (incoming + outbound) plus 70bps of FX fees will instantly see the appeal of Wise. The interest you receive on deposits, as well as a smoother onboarding process, means they’ll continue to win market share for a very long time.

In other words, trust and scale benefits will mean that the top players (WISE, EEFT, RELY… I’m excluding Xoom, IMXI, WU, and Moneygram from this cohort) will keep gaining share. Roughly half of the market is served by small players who serve a limited number of corridors (e.g., UK to Kenya). They’re the share donors, together with the legacy players.

Remitly (RELY US)

RELY sold off massively in the last week on a deceleration of growth. Let’s just say that having your target customers deported, or facing hurdles in obtaining H1-B visas, isn’t good for business. World Bank data shows that the US remittance outbound market is declining -6% YoY, which puts RELY’s 25% growth in a different light.

Starting next year, cash-originated transactions will face a 1% remittance tax, giving digital players an even larger advantage. This should further accelerate the move to digital and is not currently baked into any forecast.

But while we’re thinking about sticky customers, the market seems to have turned every company into a collection of factors. RELY fits the factor ‘decelerating growth’. This means RELY crashed and now trades at ~1.25x 2026 EV / sales. If their customers are as sticky as we think they are, that’s a buying opportunity.

Should we worry about Stablecoins disrupting the market? We don’t think so. The cost to send money across the world is in onloading and offloading money on the rails (i.e., USD to MXN conversion, occasionally having grandma pick up her cash in-store), fraud prevention, tech, and customer acquisition. Stablecoins could make transactions faster, thereby helping the entire industry because they no longer have to draw on their revolver. We’re skeptical that it can make transactions meaningfully cheaper. Everybody tells us that stablecoins will disrupt the market, but nobody has been able to explain to us how Grandma in Nepal will use USDC to buy groceries.

On December 9th, RELY will host its first Investor Day. Will they finally come up with a long-term margin target? Will the market plug in forward margins on the revenue and realize how cheap this is? We will keep you updated in our ED section.

Start your 28-day free trial

Kuppy’s Event Driven Monitor (“KEDM”) is not a financial or investment advisor and the information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute legal, accounting, or text advice or individually-tailored investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The investments discussed in this publication may not be suitable for you. You are required to conduct your own due diligence, analyses, draw your own conclusions, and make your own investment decisions. Any areas concerning legal, accounting, or tax advice or individually-tailored investment advice should be referred to your lawyers, accountants, tax advisors, investment advisers, or other professionals registered or otherwise authorized to provide such advice. KEDM makes no recommendations whatsoever regarding buying, selling, or holding a specified security, a class of securities, or the securities of a class of issuers, and all commentary is for educational purposes only. The investment examples noted are intended to provide and example of the events and data KEDM flags each week and is not representative of typical returns generated by each event or any future returns.